No Tip

Expected

Prairie Dog Brewing is on a mission to change our industry by proving that a restaurant can thrive without depending on traditional hospitality labour practices. We are a “no tip expected” establishment and our guests are under no obligation to reflexively tip their server a percentage of the bill. Instead, we invite guests to tip if and when they want to reward our team based on the quality of the overall experience. We pay our team wages that are tied to individual performance and impact. All our employees equally share the tips left behind by our happy guests through biweekly Staff Fund disbursement, which you can read more about later in this article.

How We Handle Tips

We Do Invite and Accept Tips

First, let’s be clear that our no tip expected policy is not the same thing as a “no tipping” policy. There has been a lot of confusion about this in the past and we have certainly muddied the waters with our own rhetoric. Tips are both accepted at Prairie Dog Brewing, and remain an important factor in our overall team compensation strategy. However, we don’t expect people to tip a percentage on their bill as a matter of obligation or rule, and we have a very different approach to how we distribute those tips to our team members, compared with how other restaurants do this.

Staff Fund Tip Distribution

When a guest leaves a tip at our establishment, either through our debit machines, as cash left on the table, or online with a takeout/delivery partner, those tips are pooled together by our bookkeepers on a daily basis and added to our Staff Fund. We use a spreadsheet to track daily staff fund collection from our various income sources. The staff fund is a tip pool, legally, so we also track it as a liability on our books. The current balance of our Staff Fund tip pool is always present on our financial statements, similar to the way all our accounts payables are tracked (as money owed).

Every 2 weeks, as we process payroll, we use our time punch system and staff fund spreadsheet to sum up all the hours worked by our non-owner team members during the period associated with payroll. We then dispense out 100% of the staff funds collected during that same two weeks, in a pro-rata fashion based on the hours worked by each team member. This dispensation happens as a separate, taxable line item on every employee’s pay stub. Because Staff Fund income is properly reported to the CRA, our team members are readily able to apply it towards financing mortgages and car purchases, whereas people who regularly receive tips as cash, such as through daily tip outs, often fail to track and report this income.

Now for an example. Let’s say we brought in $12,000 in staff funds for a period in which 1,200 total hours were worked by our team. Every hour worked by a team member would earn them $10 in staff funds per hour worked during this period ($12,000/1,200 hours). A full-time team member that worked 80 hours would receive an extra $800 on their paycheque (pre-tax), which works out to 6.7% of the total funds collected.

Bartender Example

While our pooled “tip out” rates, which can amount to less than 1% of weekly sales per person, might sound low compared with something like a 5% tip out for bartenders in a traditional model, where they also get a portion of whatever they brought in through their own sales, it’s important to understand that this is far from an apples to apples comparison, because:

a) The traditional bar tip out will be further divided across the multiple bartenders who worked together during those shifts.

b) Bartenders will only be collecting tip-out for sales generated during the shifts that they worked, whereas our staff fund dispensation is based on all funds earned over a 2 week period, so we’re talking about 1% of 2 full weeks worth of sales, vs perhaps 3% of 16-30 hours of sales.

To put it another way, a bartender who only works Friday/Saturday nights at a tipping establishment might only be working 15% of the total hours that their bar is open, so they are not earning 5% of that full week’s tip outs (maybe 1-3%, further divided by the number of bartenders who worked with them). So yes, during those 10-15 hours of work, this bartender might easily be making $30/hr — and sometimes a lot more, but what are they doing during the rest of the week? If they work a full 40-hour week, they would likely see a whole lot of hours where they receive little or no tips, and will still have to pay tip outs on what they did earn, which rapidly whittles down their average wages to something closer to the mid to low $20’s per hour.

The difference is that in our situation, our bartenders are already earning above the minimum wage to begin with, and after staff funds (at an $8-$10/hr dispensation), their gross wage would end up in the mid $20’s per hour, regardless of how many hours they worked with us that week. Since we are deducting taxes while other places pay out tips under the table, our employees might see a little less in net earnings, but more income over all hours worked, especially those who work a lot of hours outside of the peak periods.

The best part is that even our dishwashers and our bussers, who start out at with a $15/hr minimum wage, still earn staff funds at the same rate as everyone else, so our team wide average pay rate is already in the low-mid $20’s per hour (we aren’t at $10/hr in staff funds yet, but we are on track to get there).

At Prairie Dog Brewing, we succeed together as a team. We don’t just call ourselves a team because that sounds good on job postings. We support each other and jump into each other’s sections to help one another out. When we hear a glass fall in the dining room, everyone jumps to grab the mop and broom. We have each other’s backs. Therefore, aside from our owners, everyone on our team partakes equally in the reward of our staff funds/tips.

Like what you’re reading? If you have more time, you should check out this Eater article, which does a great job of summarizing the no tipping approaches US restaurateurs have tried out and what is and isn’t working for them.

How They Handle Tips

A visual representation of typical wage distribution in American tip-expected hospitality establishments, where median pay is charted against how much of that pay was based on tips. Servers, bartenders and waiters are clear outliers on the top end of pay scales, even though they are often paid well below minimum wage (most US states have different minimum wages for liquor servers). This disparity is far greater in places where there is no separate minimum wage for tipped liquor servers (like Alberta!).

Chart prepared by Michael Lynn with data from payscale.com.

When learning about our no tip expected model, it’s important that you understand how other hospitality businesses handle compensation so we can compare and contrast these approaches.

Typical Tip-Expected Compensation Approaches

Most restaurants and bars pay their service staff minimum wage (or less), then use tips on top of those wages to further compensate them. You can think of service staff in tip-oriented establishments as commissioned salespeople. In this type of environment, many service staff come to think of tips as their main source of income, and indeed, there are many people out there who work solely for tips (illegally).

The way tips are split up can really vary, with tip outs and tip pools being the two prevailing strategies. A handful of restaurants still allow servers and bartenders to walk away with 100% of the tips they collected each shift, but this is extremely rare.

Tip Outs

Many establishments use a “tip out” formula to split tips between the people who worked that shift. As servers leave for the day, their tips are divided and distributed to the rest of the tip-eligible team members as a percentage of that individual server’s sales, in a hierarchical fashion. A bartender tip out rate would typically be at least 5% of sales, so on a combined $10,000 sales night, the bartenders would split up $500 between them, pulled out of the total pool of tips collected by the servers, plus whatever tips they directly collected (which may also be subject to a tip out). The tip out formula may or may not include tips for hosts, managers, owners, cooks, bussing staff, and dishwashers. After all tip out cash is pulled from a servers’ winnings, the remaining money is dispensed back to them, as cash. Servers are often stuck waiting around, sometimes for hours, for their tip outs to be determined and dispensed. This is almost always unpaid time, as they’re off the clock the moment they print their shift report.

Another big problem with sales-based tip outs happens on nights where tips are unusually low. Imagine what happens in some restaurants when the kitchen food order display system goes offline during a busy dinner service. This might not be anybody’s fault, certainly not the fault of the servers, but guests would still be unhappy about receiving incorrect meals 60+ minutes after ordering, and tips would likely be smaller, even if all other aspects of service were great. On a troubled night like this, the servers may have nothing to take home after everyone else receives their tip out. We’ve even talked with servers who, at previous employers, owed money at the end of the night because their tips weren’t high enough to cover everyone else’s tip out — they literally had to pay their colleagues’ tips out of pocket! See this Reddit thread and its comments for a perspective on people’s first experiences with tip outs and gender biases at a popular Calgary summer exhibition.

Tip Pools

Tip pools are similar to tip outs because they aim to share the tips across staff in non-serving roles, like hosts, bussers, kitchen team members, etc., but instead of splitting each server’s tips as a percentage of their sales, all tips for the day (or shift) are pooled together and subsequently dispensed based on some combination of hours worked, fixed percentages of tips earned, or flat dollar amounts for supporting roles. This may be as simple as saying, “managers get 50%, bartenders get 25%, kitchen gets 5%, hosts get $10, servers take home the rest”. Tip pools can quickly run into trouble, though, such as when some staff only work during slower times of the day, so General Managers often try to tailor their methods to ensure a “fair” distribution.

As you can probably imagine, there is no shortage of opportunities for things to go wrong with both tip outs and tip pools, and they generally require a great deal of tracking on the part of management. Tip disbursement calculations may also lack transparency (all tips collected and redistributed through pools need to be reported as taxable income on employee pay stubs, upping the stakes and tracking burden). While the Prairie Dog Brewing Staff Fund is technically a form of a tip pool, we handle tips quite differently than the typical restaurant approach, and we’ve done our very best to distribute funds as equitably and transparently as possible.

With tips being such an important part of service staff income, tip distribution can be the greatest source of conflict and drama in a lot of tip-oriented establishments, so why go to all this trouble? Is it because tipping actually works? It might be time for a reality check.

Tip Expected Doesn’t Make for Better Service

The Public Perception of Tipping Is Based On A False Narrative

When reading our occasional negative guest reviews, our no tip expected philosophy often receives most of the blame for our failures. We are not alone in this, many US restaurants have experienced the same trend in reviews after changing models. As North Americans, we were indoctrinated to believe that tips act an incentive for servers to provide great service. When we dine at a restaurant that isn’t expecting a tip, or where service is included in menu pricing (ours isn’t), we observe that entire experience with a more critical eye simply because something is different, possibly finding links between service issues and the restaurant’s tipping policy that don’t actually exist.

Throughout the following discussion, we talk about several key ways that this tipping narrative is flawed, but it’s best to keep in mind that much of our planet operates just fine without any tipping, including plenty of Michelin star restaurants. Tipping a person in other countries might even be seen as pompous and offensive, because that part of the world understands the underlying paternalism that perpetuates the North American tipping model, which also has deep roots in slavery and racism.

Several key reasons why the tipping narrative is flawed are found below, but first we need to address our negative reviewers’ concern. No, the fact that your beer wasn’t refilled instantly or that you had to wait to pay your bill was not related to our no tip expected approach. In fact, most of our service issues come down to 2 things — either that we were short handed at the time, or that we have human beings on our team who are continuously learning their craft and occasionally have a bad day.

Service Is A Small Factor, At Best

The assertion that tips reward the “best” servers for the quality/promptness of their service is laughable, and this is a well known fact within the ownership side of our industry. Studies have repeatedly found that service has only a small impact (2-4%) on average tipping rates in tip-expected establishments, whereas things like gender (both of guest and of server), physical appearance (including sexualized uniforms), and flirting have a greater impact. In a no-tip-expected establishment like Prairie Dog Brewing, we believe tipping rates are a reasonably good indicator of our overall team’s performance, but still not very indicative an individual server’s abilities (quality of service can be impacted by so many things that a server has no influence over), so we use tips as a reward for our entire team to share in equally (as a per hour amount with our Staff Fund), rather than individually.

Read this 2013 research paper for an extensive analysis of the factors affecting tipping behaviour in restaurants.

Tip Earning Rates Are Influenced by Time Of Day

The vast majority of the tips earned by a server are simply a function of how busy the restaurant was at the time they were scheduled (how many tables they took payments for), and the time of day they worked (eg. people spend a lot more at dinner time than at lunch time). Team members who work on busy nights earn the most, except on rare occasions where a daytime guest leaves a spectacularly large tip.

What about the people who work during traditionally slow times or at times where average spends are lower? Weekday daytime servers are often expected to set up the restaurant, then handle a short, albeit intense lunch rush, then spend the remainder of their afternoon answering the phone and door, cleaning the restaurant and preparing it for dinner services and events, pouring their own drinks from the bar for the guests that come in for happy hour, and expediting food for tables and delivery drivers, often with little supervision or backup from other teammates, and with fewer opportunities for uninterrupted breaks. Why should this superior multitasker, who knows how to do all these jobs well enough to work unsupervised, earn far less per hour than a colleague who is regularly scheduled for a single role on busy nights with higher average spends by guests, who also has 10 other staff to back them up on the floor? Of course the first person should be paid more!

Moreover, chances are high that a daytime server works those hours because they have a family to take care of on evenings and weekends, whereas the Friday night servers are often young, single people without dependents. Recognizing that our team members are human beings, we aim to set them up to succeed based on their individual talents and needs, then reward their individual ability and impact directly through wages, as the foundation behind our model.

Compulsory Tipping Drives Perverse incentives

A restaurateur might judge their “best” staff not based on the quality of the service they provide, but by who makes them the most money from each guest. When guests are obliged to tip as a percentage on a bill, the incentive is there for a server to maximize the value of that bill to gain a larger tip for themselves. Yes, we are all for-profit businesses, and the financial pressures of today require us to maximize our earnings or we won’t stay in business very long, but the standard tipping model can cause staff to go too far.

Servers and bartenders are often compelled to use deceptive and sometimes dangerous tactics to maximize guest alcohol intake and “loosen up” their spending decisions. For example, a server might be quick to get drinks in guest’s hands as they arrive, but then withhold menus and food ordering long enough to get guests tipsy, all so they will more be more impulsive when asked about upsells.

Reflexively offering “one for the road” shots whenever a bar guest asks for their bill at some of our tip-expected competitors is common and encouraged by management. While we literally make our own alcohol and love to share it with our guests, we really do believe in fostering responsible social drinking, and we take our duty of care towards our guests and the surrounding community very seriously. While onboarding experienced front of house team members from other establishments, we frequently receive comments like, “Really? Nowhere else that I’ve ever worked has cared about this”, which breaks our hearts, but it all goes back to the tip-based approach of restaurants and bars today.

Are There Downsides to Not Expecting Tips?

It wouldn’t be fair to get on our high horse and tell you about all the things we like about our model, without also talking about the challenges it presents, which any restaurateur who might be considering making the switch should be aware of.

Fighting Preconceived Notions About Tips

The hardest thing about operating with a no tip expected model is having to constantly operate in conflict with people’s biases about tipping. Both the tradition and popularity of tipping in our culture have led to the false narrative described earlier, and anytime that narrative is challenged, a lot of people simply resort to using logical fallacies to make their arguments (eg. appeal to popularity – if everyone else is doing it, it must be the right/best way).

As we discussed earlier, our no tip expected policy is usually the first thing people blame for all of our shortcomings and failures, simply because it is “different” from what they know. It can be exhausting having to educate our guests, staff and community about this.

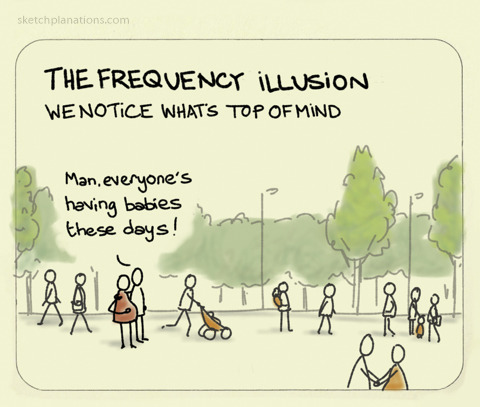

Team Wages and the Frequency Bias

The most popular bias in the restaurant industry is probably the “frequency bias“. A great example is when a person working at a tip-expected establishment starts believing that they earn a lot more (through tips) than they actually do, based on a handful of shifts where they were tipped spectacularly, ignoring all the ones where they weren’t. These people tend to brag to their friends and family, grossly overstating their true rate of pay because they didn’t track their earnings or the total amount of time they spent at work — they truly have no idea of what they actually make per hour, especially over a reasonable timespan (weeks to months).

Eg. “I took home $300 in tips that night. I only worked 5 hours, so that’s like $60 an hour on top of my minimum wage — $75 per hour!”. Yes, that might happen once in a blue moon, but what do the rest of your days and weeks look like, and how many unpaid hours did you work?

Our team members are often subjected to this kind of bragging of half-truths from members of our industry, and we have lost good people simply because they were misled into believing that they could earn a great deal more in other restaurants than they do at Prairie Dog Brewing. Whether it be at a tip-expected establishment or not, patrons are only willing to pay so much for food and beverages, and all business is a zero-sum game, so if any staff member is making a great deal more money at a different restaurant with similar menu prices to our own, it has to be at the expense of something else, like the wages of non-service staff, a lack of health and wellness benefits, or a lack of food quality/safety for the guests at those establishments.